California is one of several states where recreational marijuana is legal despite its federal classification as a schedule one narcotic.

State law and federal law also conflict on immigration. That issue became even deeper when, on January 1, 2018, California declared itself a sanctuary state thus running directly afoul of federal immigration law.

Who wins such conflicting arguments? Perhaps the federal government as the United States Supreme Court has, on multiple occasions, upheld the ability of federal officials to enforce federal law which conflicts with state law.

How these specific issues can collide is interesting. In every state where it’s legal, marijuana laws only apply to US Citizens. Those here illegally, or even those with a green card, cannot use or possess marijuana, even medically, as they would violate federal law. That’s a deportable offense.

Many Americans debate the legitimacy of marijuana use however few can dispute there’s widespread abuse. Not surprisingly, substance abuse disguised as medical necessity is nothing new.

1918: The Volstead Act was enacted to carry out the intent of the 18th Amendment which established prohibition in the United States. The Anti-Saloon League's Wayne Wheeler conceived and drafted the bill, which was named for Congressman Andrew Volstead, Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee at the time.

While the 18th Amendment prohibited production, sale, and transporting "intoxicating liquors", it didn’t define "intoxicating liquors" or provide penalties. It granted both the federal government and the states the power to enforce the ban by "appropriate legislation".

That bill was introduced in Congress in 1919, however it was vetoed by President Woodrow Wilson because it also covered wartime prohibition. The veto was overridden by the House on the same day, October 27, 1919, and by the Senate one day later.

That bill provided, "no person shall manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, or furnish any intoxicating liquor except as authorized by this act." It didn’t specifically prohibit the use of intoxicating liquors. The act defined intoxicating liquor as any beverage containing more than 0.5% alcohol by volume and superseded all existing prohibition laws in effect in states that had such legislation.

Prohibition had three distinct purposes: prohibit intoxicating beverages, regulated the manufacture, sale, or transport of intoxicating liquor (but not consumption) and ensure an ample supply of alcohol and promote its use in scientific research and in the development of fuel, dye and other lawful industries and practices. Farmers were allowed to produce wine for their own consumption and priests, ministers and rabbis to serve it during religious ceremonies.

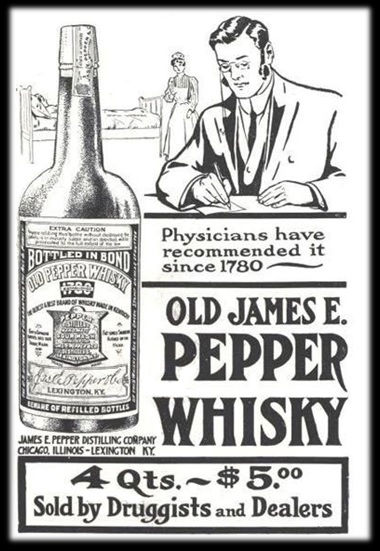

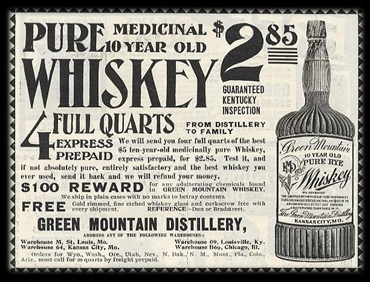

The Treasury Department authorized physicians to write prescriptions for medicinal alcohol. While it now seems absurd a medical doctor would suggest a can of Coors to treat cancer or a bottle of Sailor Jerry for COPD, licensed doctors, with pads of government-issued prescription forms, once advised patients to take regular doses of hooch, primarily whiskey, to stave off a number of ailments including cancer, indigestion and depression.

For $3 ($37 in 2017 dollars) medicinal alcohol patients could get a prescription and for another $3 or $4 to have it filled with a pint of booze. Many historians now agree that while there may have been some who were being prescribed for a perceived medical need, many more physicians and pharmacists got into the business just to make a few bucks.

Of course criminal enterprises cashed in. Street gangs, which had all but been eradicated in the early 20th century, saw a resurgence in membership and violence. Despite suggestions that legalization would break up criminal gangs, the Mafia didn’t vanish after the prohibition repealed on December 5, 1933.

Now, history may be repeating. Like the Mafia who didn’t simply walk away when the market changed, violent cartels may be taking advantage of legalization. According to the United States DEA 2016 National Drug Threat Assessment, much of the retail marijuana trade is handled by street gangs and other criminal groups in the US.

On September 27, 2017, Mike Vigil, former director of international operations for the DEA, told Business Insider, "The cartels use gang members. They use individuals living in the United States to basically do the distribution and the logistics."

That point may be reinforced by a January 19, 2018, Newsweek report which stated the pot industry and farms of Northern California, Calaveras County is mentioned specifically, is being taken over by Mexican drug cartels. Whether this coincides with 2017 setting a record for murders within Mexico remains to be seen.