Dec 2004

After almost 30 years in this profession not much shocks me. Then came revelation that a member of law enforcement was identified in a brutal killing of an innocent female back in the 1980’s. The first question that comes to mind is how did someone working within the very agency investigating the crime manage to escape detection for so long?

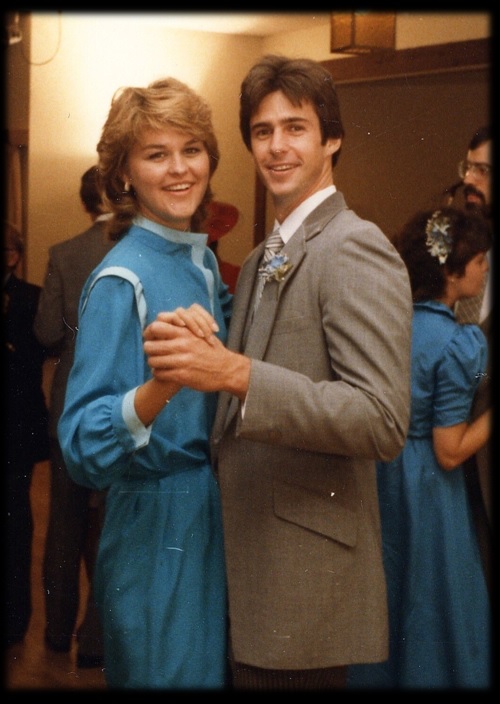

1985. The victim, Sherry Rasmussen, was a young woman with a bright future. Brutal overkill suggested the horrible crime was fueled by rage. Biting was also involved. There were no witnesses.

Initial evidence suggested a botched hot prowl. That led detectives to focus on a pair of burglars who’d been working the neighborhood. Then a different picture began to emerge. Electronics had been gathered and stacked up at the top of the stairs but evidence showed a struggle began upstairs and ended in homicide on the ground level. So why didn’t the electronics get knocked over?

On top of the record player was a thumb-shaped bloodstain with no print suggesting whoever left it was wearing gloves. It was later determined the blood belonged to the victim, suggesting the equipment had been stacked after the murder.

The only things actually missing were the victims BMW car and her framed marriage license.

The murderer shot the victim in the chest with a .38 at close range. Gunpowder burns on a quilt suggested the killer had muffled the shot. Clearly, the killing was deliberate.

Experience told the detective’s that bites during struggles are more commonly inflicted by women, while most burglars are men.

Despite serological evidence that could link a suspect to the crime, limits of forensic science at that time prevented a DNA match. So, like many other murder cases, the case sat dormant - in this case for decades.

At some point the suspect probably began to think the crime was forgotten. If so, then came an unfortunate turn of events. With the municipal murder rate in decline, detectives now had more time to go back and reexamine some old cases - among them, the brutal 1980’s murder.

Armed with new techniques, detectives decided to give the case a fresh look.

If hope came from thinking improved DNA techniques could identify the killer, the crime lab soon delivered disappointing news. There was no match in the CODIS database. The criminalist then reached a conclusion that undermined the initial burglary theory and sent the case in an entirely new direction; saliva collected at the crime scene came from a female.

Revisiting the original case reports, detectives soon discovered a reference to a “third-party female" having harassed the victim at her job and residence before the murder.

The third party female was ultimately identified as a past girlfriend of the victim’s new husband. Her name: Detective Stephanie Lazarus, of the Los Angeles Police Department.

A distinguished police officer with more than twenty years of service, Lazarus was an expert in stolen art and was assigned to the prestigious Robbery Homicide Division – the same unit tasked with investigating cold case murders. Many of the cold case detectives knew Lazarus personally as her office was directly across the hall and they often rode the elevator with her.

Detectives now had a dilemma. Not only was her husband a detective working in the nearby Commercial Crimes Division, she may have had other friends who could have tipped her off. If she were the killer, she could improve her defense or even flee. If she weren’t they could unintentionally damage the career and reputation of a fellow officer.

To keep things covert, detectives only referred to Lazarus as "No. 5" and worked on the case after hours or behind closed doors. They also developed cover stories as to why they needed to examine 20 year old personnel records.

Detectives knew a patrol officer could know how to make a premeditated murder appear as an interrupted burglary. As all LAPD patrol officers work in two officer cars, it would be best to do it on a day off. Departmental records confirmed Lazarus was off on the day of the crime.

As detectives began looking into aspects of her life during the mid-1980s, a detective recalled most LAPD officers preferred a .38 as their off-duty carry gun. An officer would know better than to use their duty gun so it made sense to use a backup. A check revealed Lazarus once owned a .38 but reported it stolen 13 days after the murder.

With Lazarus now the prime suspect, a choice had to be made between obtaining a warrant to collect DNA thus tipping Lazarus off, or to discreetly collect a voluntarily discarded sample. Choosing the latter, detectives retrieved a cup she had discarded while running errands off-duty. A forensic follow up matched the crime scene DNA.

With the Chief and the District Attorney fully briefed, dozens of officers gathered with vague information about an outside the city search warrant they would be executing. Meanwhile, detectives pre-selected for their lack of personal connection to Lazarus, called her from the Parker Center Jail claiming a prisoner wanted to talk about an art theft.

After Lazarus checked her gun and entered the interrogation room, detectives Greg Stearns and Dan Jaramillo explained they were trying to tie up loose ends in an old murder case and her (Lazarus) name had come up in the investigation. Detectives claimed they wanted a private setting because they didn’t want her private life to become the subject of office rumors. Detectives knew they’d have to tread carefully since Lazarus was well aware of interview techniques and her right to remain silent.

Fortunately, Lazarus chose to talk. At first she claimed to remember very little but then gradually revealed more and more information, including acknowledging she had visited the victims condo. When Lazarus got up to leave the room she was immediately arrested. Once in custody the teams of detectives began searching her home and car.

In his opening argument at her murder trial, prosecutor Shannon Presby summed up the case as, "A bite, a bullet, a gun barrel and a broken heart. That's the evidence that will prove to you that defendant Stephanie Lazarus murdered Sherri Rasmussen."

In March of 2012, the jury deliberated several days before convicting Lazarus of first-degree murder. She was sentenced to 27 years to life and is serving her sentence at the Central California Women's Facility.

Lazarus appealed the conviction claiming that the age of the case and the evidence denied her due process. She also alleged that the search warrant was improperly granted, her statements in an interview prior to her arrest were compelled, and that evidence supporting the original case theory should have been admitted at trial.

In 2015, the guilty verdict was upheld by the California Court of Appeal for the Second District of the state.

Sherry Rasmussen and John Ruetten

Detective Stephanie Lazarus

Stephanie Lazarus listens to court testimony during her murder trial