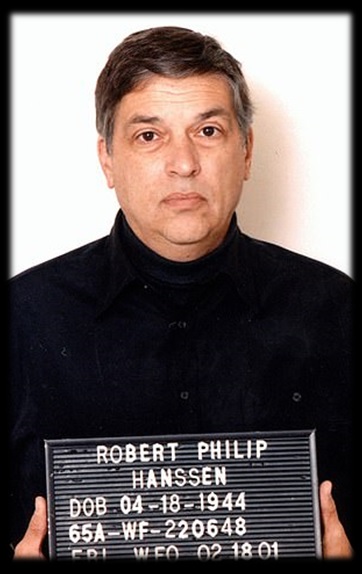

If, in the cloak and dagger world, spies are measured by damage they inflict, few match Robert Philip Hanssen.

After earning his BA in chemistry in 1966, Hanssen applied for a position as a cryptographer for the National Security Agency (NSA). When budget cuts eliminated the position, he earned his MBA in accounting and information systems. In 1971, Hanssen took a job with an accounting firm but soon quit to join the Chicago Police Department as an internal affairs investigator.

Hanssen left Chicago in January 1976 for the FBI. His first assignment was Gary Indiana.

In 1979, Hanssen was in New York City compiling a database of Soviet intelligence activity. That same year, he approached the Soviets and offered information on FBI activity as well as naming Soviet double agents. Among the most damaging betrayal was to General Dmitri Polyakov, an informant who’d passed information to the CIA while in the Soviet Army. Inexplicably, the Soviets didn’t use his information until Polyakov was outed a second time in 1985, this time by CIA turncoat Aldrich Ames. That led to Polyakov being executed.

In 1981, Hanssen transferred to FBI headquarters to oversee wiretapping and electronic surveillance. He soon developed training to become a computer expert.

In 1984, Hanssen transferred to the FBI's Soviet Analytical Unit to study, identify and capture intelligence operatives.

In 1985, Hanssen transferred back to New York. That same year he sent an anonymous letter to the KGB offering his services for $100,000. For credibility, Hanssen identified three KGB double agents: Boris Yuzhin, Valery Martynov and Sergei Motorin. Hanssen was unaware all three had already been exposed by Ames.

The Soviet spies were recalled to Moscow. Martynov and Motorin were executed. Yuzhin was imprisoned. Because Ames was blamed for the leak, Hanssen wasn’t immediately suspected.

By 1987 the FBI circled back to identify who outed the three Soviets. Ironically, Hanssen was assigned to find the mole. Keenly aware he was looking for himself, he crafted a report that covered his tracks but listed Soviets who’d contacted the FBI about double agents.

In 1989 Hanssen sold extensive information about American radar, spy satellites, signal intercepts and a top secret spy tunnel beneath the Soviet embassy. On two occasions, Hanssen sold the Soviets a list of American double agents. For his betrayal Hanssen received $5000.

In 1990, Hanssen's brother-in-law, also an FBI employee, recommended Hanssen be investigated after his wife discovered a pile of cash on a dresser in Roberts house. For reasons unknown the FBI didn’t act on the tip.

Hanssen broke ceased contact with the Soviets in December 1991 when the USSR collapsed.

The following year Hanssen approached a diplomat in the garage of the Russian embassy. Introducing himself as a "disaffected FBI agent" offering his services as a spy, Hanssen used his former Soviet name of Ramon Garcia. Smelling a trap, the Russian drove off. Shortly thereafter, the Russians, believing Hanssen was a triple agent trying to set them up, filed a protest with the State Department. Despite having shown his face and revealing his FBI affiliation, the Bureau didn’t investigate.

In 1993, Hanssen hacked into the computer of fellow agent, Ray Mislock, then printed out a classified document. Hanssen showed the document to Mislock exclaiming, "You didn't believe me that the system was insecure."

FBI management launched an investigation. When questioned, Hanssen claimed he was demonstrating flaws in the security system. Mislock later theorized Hanssen was trying to see if he was being investigated then invented the document story to cover his tracks.

In 1994, Hanssen requested to transfer to the new National Counterintelligence Center. He changed his mind when he learned he’d be polygraphed.

Three years later, convicted FBI mole Earl Edwin Pitts told the Bureau he suspected Hanssen was dirty due to the Mislock incident. Pitts was now the second FBI agent to suggest Hanssen was a mole, but still no action was taken.

Hanssen eventually became so emboldened he began using his real name to search FBI computers to see if he was under investigation. Finding nothing, Hanssen resumed spying after eight years without contact with the Russians.

In retrospect, two moles inside the U.S. intelligence establishment simultaneously — Aldrich Ames at the CIA and Hanssen at the FBI — helped Hanssen remain undetected.

Ames arrest in 1994 explained many of the intelligence setbacks of the 80s however, as Ames didn’t work for the FBI, the embassy tunnel leak remained unsolved. In response, the FBI and CIA formed a mole-hunting team codenamed "Graysuit." The operation cleared several suspects and located a sellout CIA turncoat named Harold James Nicholson however Hanssen escaped notice.

By 1999, the FBI was well aware they still had a serious leak and were growing desperate to find it.

In a fairly unprecedented move, the bureau paid a Russian double agent seven million dollars for the moles files. Among those items was a recorded conversation from 1986. As he listened to the tapes, FBI agent Michael Waguespack recalled the moles voice as familiar but couldn’t positively identify it.

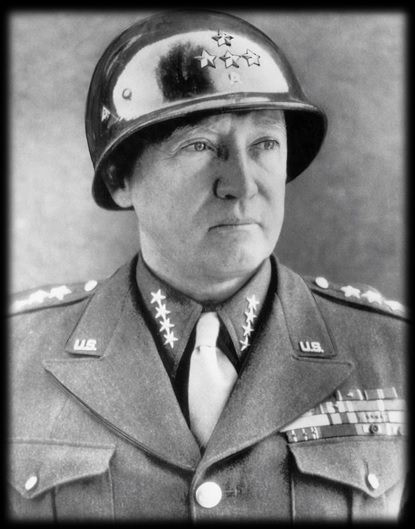

Investigators eventually found references to the mole using a quote from General George Patton about, "purple-pissing Japanese." FBI analyst Bob King remembered Hanssen often used that same quote. Agent Waguespack listened to the tape again and identified the voice as Hanssen.

Things now began to fall into place. Locations, dates and cases were matched with Hanssen's known activities. Fingerprints collected from a trash bag in the file proved to be Hanssen's.

Still needing more evidence, in December 2000, the FBI promoted Hanssen and gave him an assistant, Eric O'Neill – an undercover agent. O’Neill soon obtained the PDA Hanssen routinely used. A forensic search of the device revealed a treasure trove of evidence and gave the bureau its, "smoking gun."

By now Hanssen suspected something was wrong. In February 2001, he applied for a job at a technology company. In his last letter to the Russians, Hanssen said he’d been promoted but "Something has aroused the sleeping tiger."

Despite his paranoia, Hanssen attempted one more contact. On February 18, 2001, Hanssen drove to a park and placed a piece of tape on a sign - a signal to the Russians he was dropping information. Hanssen then placed a sealed bag of classified material under a wooden footbridge.

Surveilling agents rushed in and arrested Hanssen. As he was being arrested Hanssen quipped, "What took so long?"

With Hanssen in custody, the FBI continued to monitor the drop site for two days. When Russian agents didn’t collect the bag, the Justice Department announced Hanssen’s arrest.

On July 6, 2001, Hanssen pleaded guilty to fifteen counts of espionage. On May 10, 2002, he was sentenced to life without parole. In addressing the court Hanssen said, "I apologize for my behavior. I’ve hurt so many.”

Today Hanssen serves his sentence at in solitary confinement at ADX Florence, the "Alcatraz of the Rockies," and "Supermax." The facility is a modern super-maximum security federal prison located in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains near Florence, Colorado.

Opened in 1994, the ADX Supermax facility was designed to incarcerate and isolate criminals deemed as being too dangerous for the average prison system.

Stripped of his freedom and even his identity, Robert Hanssen will live the rest of his life as Prisoner # 48551-083.

Disgraced FBI Special Agent Robert Hanssen