Unfortunately the sport wasn’t new. Bull and bear fights date back to the Roman Empire. In the middle-ages London constructed lavish amphitheaters known as “bear-gardens” to host the events.

The Spanish probably began holding battles between California Grizzlies and wild bulls not long after arriving in San Francisco in 1776.

In 1816, the Russian ship Rurik dropped anchor in San Francisco Bay and the governor of California invited the crew to observe a fight. Spanish troops, “are sent out into the wood for a bear, as we would order a cook to fetch a goose,” marveled the ship’s captain, Otto von Kotzebue. After finding a suitable bear, the troops used multiple lariats to secure the animals legs to render it helpless.

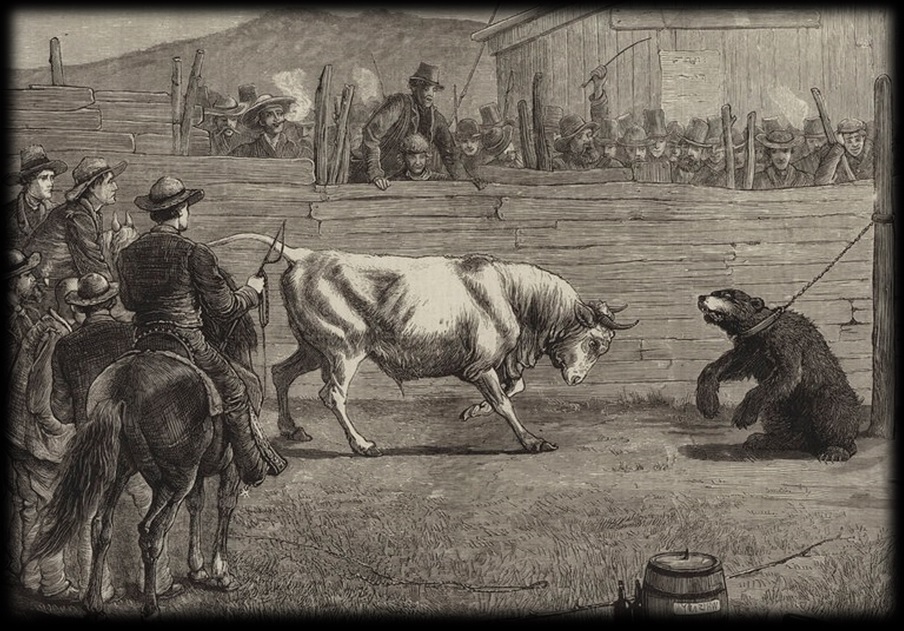

California bull and bear arenas were called pits and were constructed of split-board fencing and reinforced with heavy logs and adobe. For families, a raised viewing platform was constructed for women and children. Armed men remained on horseback outside the barricades in case the bear attempted an escape.

Events were held on Sundays after church. In the California Pastoral, a chronical of life in the Golden State during the 19th century, historian Hubert Howe Bancroft described the events: “A bull and bear fight after Sabbath services was indeed a happy occasion.” Referring to the bear, Bancroft said, “It was soul-refreshing to see the growling beast of blood chained by one of its hind feet, as to leave it free to use its claws and teeth.”

Bull versus bear wasn’t the only blood sport on the venue. Like a modern concert with an opening act, a typical bull and bear fight often had an undercard of cockfighting and dogfighting to wet the crowd’s appetite for death.

Other strange pregame activities were also held - horsemanship, sharpshooting, or lassoing - anything to prove the cowboy had the right stuff.

One popular form of horsemanship involved burying a rooster in the dirt up to its neck. Then, a horseman charged the fowl at full speed and in one fell swoop took the birds head off with a sword. If he succeeded the crowd went wild. But, according to Bancroft, “if the rider failed he was greeted with derisive laughter and was sometimes unhorsed with violence, or dragged in the dust at the risk of breaking his neck.”

Then came main event. With the audience barbequing and the smell of grilled meat permeating the air, the half-intoxicated crowd usually jumped to their feet cheering when the animals were escorted into the arena by short coat, sash wearing horsemen.

According to Bancroft, the bull and bear were often tethered by a rope, “short enough to keep the animals in each other’s company.” To get the bear, “into a fighting spirit” the chained bear had been set upon by dogs and repeatedly bitten just before being led into the arena. Bulls were poked with banderillas and further agitated by fireworks.

As the crowd cheered to release the beasts, the officiator climbed onto his raised platform, women and children behind him, then fired a pepperbox pistol in the air to start the contest.

Reporters of the era said bears often assumed a defensive posture on its hind legs. The bulls, most of whom weighed 1200 pounds or more, were generally the first to attack, setting upon the bear by charging with its large, muscular head down and horns aimed directly at the grizzly.

Despite a significant weight difference, piercing horns and the bulls ability to charge at almost 40 mph, audiences generally understood grizzly held the advantage. Using long, strong arms the bear could clamp its razor sharp claws into the bulls head then sink his long teeth into his neck.

“I was present,” stated a spectator named Arnaz in the pages of California Pastoral, “when a bear killed three bulls.”

Bancroft recalled one event where the bear grabbed the bull by the head then bit off the bovines tongue. The crowd went wild. At such times cowboys would break up the fight to save the bull and prolong the drama.

According to Bancroft, there were occasions where a single grizzly would fight several bulls consecutively. “Sometimes the bull came off victorious, and at other times the bear, the result depending somewhat on the ages of the beasts.”

As dreadful as the average fights were, they paled in comparison when compared to a gladiatorial spectacle described in the April 1859 issue of Hutchings California Magazine. The piece reported that in 1851, a nearly weeklong bull and bear fiesta at Mission Santa Clara featured not only 12 bulls and two grizzlies but a “considerable number” of Native American’s - four of whom were killed.

While records of when it all ended are sketchy, it appears California’s last bull and bear fight may have been occurred in Castroville in September 1867.

Today such a spectacle isn’t just illegal but morally repressible and visually traumatizing to anyone without a brutal, sadistic nature. But that doesn’t mean the gruesome sport is completely forgotten. The gory 19th century fights inspired the modern day colloquialism of Wall Street: “bull markets and bear markets.” Everything else is just history.

When 597 Was in Vogue

California Penal Code, Section 597(a) makes it illegal to maliciously and intentionally maim, mutilate, torture, or wound or kill a living animal.

Prior to the 16th century more than 10,000 majestic grizzly bears roamed the vast undeveloped wilderness of California. Admired for its size, beauty and strength, the California Grizzly - a now extinct subspecies of the grizzly bear family – was the symbol of the Bear Flag Republic, a short-lived attempt at establishing California as an independent nation in 1846.

Unfortunately, the bears fell from grace.

By the 19th century, California Grizzlies were sought for their intrinsic fighting qualities, especially when coerced into combat with a bull. Things turned ugly when the massive beasts became entertainment for blood thirsty crowds on Sunday afternoons.